Robotics;Notes is a love letter to robot and mecha anime. And of all the SciADV subseries, Robotics;Notes might just have the most sources of inspiration. From Hollywood movies like The Right Stuff, to shonen manga like JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, to tokusatsu franchises like Ultraman, to Japanese mecha series like Gundam, Gunbuster, and Neon Genesis Evangelion, to even the robot anime that started them all—Astro Boy.

There’s a line from Phase 1 where Akiho describes the in-series Gunvarrel anime as being the culmination of all robot and mecha anime predating it, with Gunvarrel cherry-picking different elements from all its predecessors. Robotics;Notes itself is very much the same, taking in so many different elements from dozens of robot and mecha series that came before it.

Yet despite Robotics;Notes very obviously being a love letter to the genre, most existing analyses of the title don’t touch very much on its engagement with all its sources of inspiration. And I suppose this is likely because the average person who goes through SciADV typically isn’t a huge mecha nerd—myself included.

Personally, I’m nowhere near comfortable enough to talk extensively about most of Robotics;Notes’s sources of inspiration—at least to the level I’m comfortable talking about SciADV. But there is one exception—that being none other than Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy (aka Tetsuwan Atom), which is arguably the most influential anime and manga of all time. In this article, I’ll go over where Robotics;Notes pays homage to Astro Boy—most notably, in Phase 6.

And it should go without saying, but the remainder of this article will contain spoilers for both Robotics;Notes Elite and Astro Boy itself.

Anyhow, at even just a preliminary glance, it should be extremely obvious that Tezuka’s classic was a massive source of inspiration for Robotics;Notes. Right at the beginning of the story, Akiho credits the start of this mass appeal and love for robots as having emerged from what’s known in-universe as “Astro Kid,” which is very obviously the in-story equivalent of Astro Boy. And throughout the rest of the story, Robotics;Notes features several plot points based off those seen in Astro Boy.

Astro Boy has a number of different stories centered around the use of the sun to destroy Earth, though the most iconic and memorable of these is undoubtedly in the final episode of the 1963 Astro Boy anime, “The Greatest Adventure on Earth.” In this episode, Napoletan’s forces plot to take control of Earth while a sun spot heats the planet up like crazy. As a result of the chaos from the rising temperatures, humanity forsakes Earth, leaving on rockets to wander outer space for an entire year. In order to stop the sun from destroying Earth, Atom flies on a rocket straight into the sun to return it to normal and save the planet.

In Robotics;Notes, Project Atum is fundamentally about replicating the same general circumstances as the final episode of Astro Boy: artificially creating a solar corona to cause a massive magnetic solar storm to wreak havoc on the planet. All the while, the wealthiest of people would hide underground or go into space—the latter of which is rather reminiscent of what happens in Astro Boy. The fact that Project Atum is called what it is should also make it pretty clear that this plan is a reference to Astro Boy, or Tetsuwan Atom as it’s known in Japanese. Kimijima being Project Atum’s mastermind is also quite fitting in that he’s somewhat similar to Napoletan; they are both artificial beings seemingly derived from a real human brain—though in Napoletan’s case, he mistakenly believes himself to be a cyborg with a human brain when he’s actually 100% robot.

Additionally, if you take a quick glance at the final episode of Gunvarrel, you’ll immediately realize it’s basically the inverse of “The Greatest Adventure on Earth.” Earth itself is in practically identical circumstances across both shows, with a solar storm threatening to eradicate humanity and leave nothing behind but robots. But in Astro Boy, Atom flies into the sun and “sacrifices” himself to stop it from destroying Earth, whereas in the last episode of Gunvarrel, the robots collectively cause what is basically the destruction of almost all organic life on the planet by committing mass suicide, jumping into a furnace powering a massive laser that makes the sun explode. So very obviously, both Project Atum and the final episode of Gunvarrel are largely inspired by Astro Boy.

But in addition to narrative similarities, you’ll find some genuine thematic parallels as well—most prominently in Phase 6.

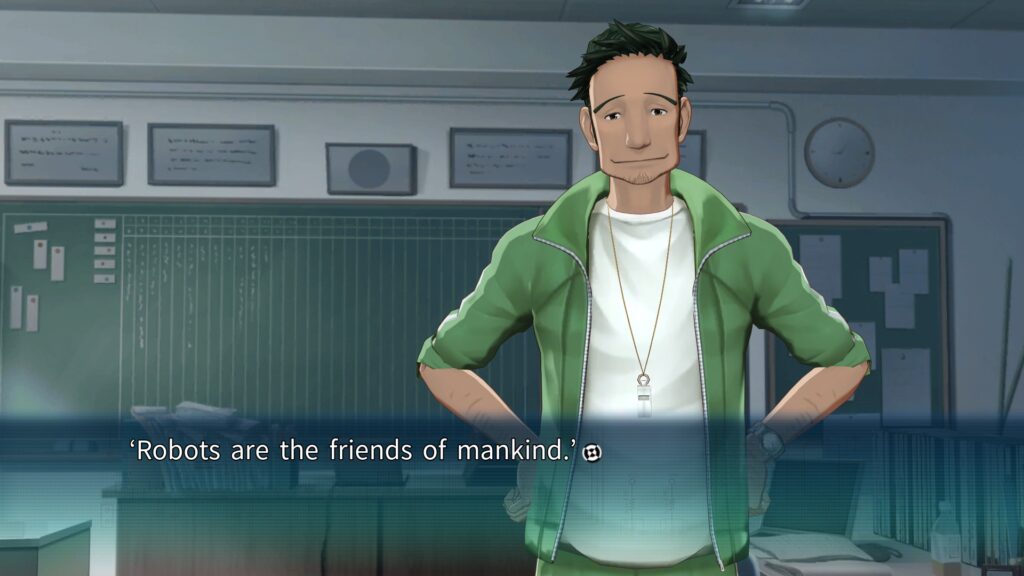

A recurring line from all throughout Astro Boy is, “Robots were created to be friends with humans.”

This line would come to fundamentally define Astro Boy for what it was—a work of extraordinary humanism: the belief that all lives are sacred and all people are equal. At its core, Astro Boy is a story of universal love and pacifism. It’s a story that stood firmly against racism, discrimination, xenophobia, and warfare of all forms.

Even though Robotics;Notes and SciADV at large never came to have these sorts of anti-racist or anti-war themes, the iconic line itself would still come into play in Robotics;Notes Phase 6 with a far more literal meaning, centered around the value that artificial existences like robots can hold for people.

Robotics;Notes Phase 6 is Junna’s chapter—a character study of both Junna and her grandfather, Fujita. It’s the story of a girl whose childhood traumas left her terrified of anything to do with robots… and also the story of her grandfather, who himself became disillusioned by and afraid of robots out of the fear of hurting anybody ever again. Phase 6 might genuinely be one of my favorite chapters from the entirety of Robotics;Notes, because the chapter itself is effectively a love letter to Astro Boy specifically, and it carries the same exact message: that robots are humanity’s friends.

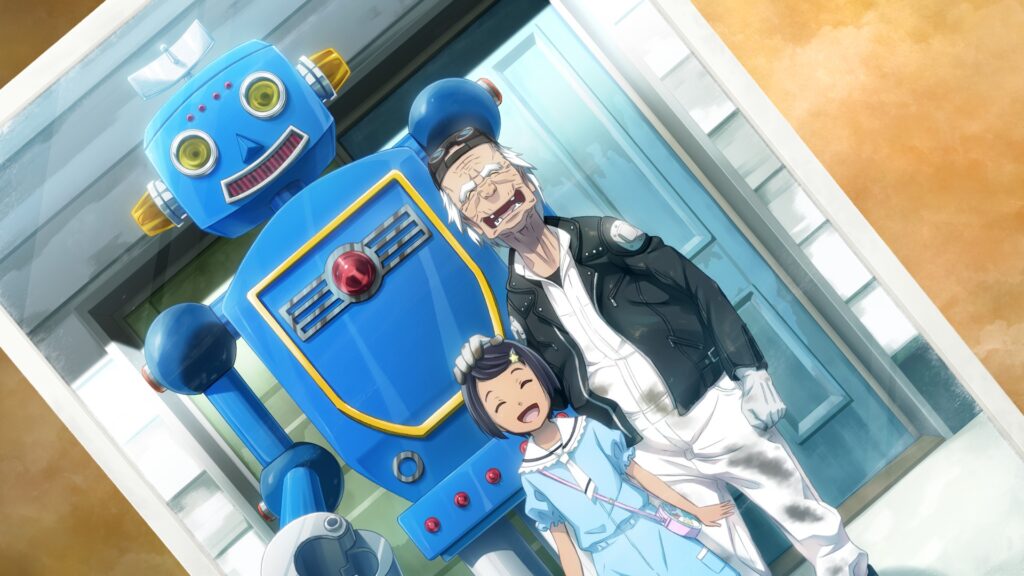

Fujita, for the longest time, firmly operated under this belief. After all, in-universe, he was the final disciple of Dr. Jiro Aizawa, the real-life legend widely hailed as the father of toy robotics in Japan, who also happened to be a close collaborator and friend of Osamu Tezuka, the author of Astro Boy. Fujita even modeled and named his robots in honor of Dr. Jiro Aizawa.

But the incident wherein Yoshiro-kun fell on Junna, crushing her, completely changed everything for both Junna and Fujita. It gave Junna a decade-long fear of anything to do with robots or her grandfather. And it gave Fujita even greater wounds to his heart—an immense guilt that entirely overturned his ideology that robots were humankind’s friends. After the accident, Fujita started believing that humans and robots should forever be completely segregated and that children should never go anywhere near robots.

In the end, the fundamental contention of this chapter is between whether robots are just a bunch of worthless, programmed, artificial pieces of junk, or if they hold meaning and can be legitimately regarded as “friends of humanity.” Both Junna and Fujita lean toward the former of the two standpoints for the majority of the chapter—with the ways their traumas greatly affected the way they viewed robots.

For Junna, there are three turning points that truly make her change her mind. The first is Kaito showing her a photo of herself, her grandfather, and Yoshiro-kun all together and all smiling—as if Yoshiro-kun gave them the greatest joy in the world. The second turning point for Junna was when she rewatched the recording of GunBuild-1’s public demo, where she was able to witness the reactions of everybody present for the event and see for herself how so many people—children, adults, and the elderly alike—found value, meaning, and excitement in the proposition of a moving giant robot. Not a soul among the audience was afraid of GunBuild-1 the way Junna was; rather, they were inspired by it, motivated to attend out of awe for its splendor. It was here that Junna understood Fujita’s original ideology—artificial though they may be, robots are indeed the friends of humanity. And on top of that, the idea that this single giant robot was the culmination of so many different people’s dreams over the course of a decade—her grandfather’s included—moved her to tears, especially when she realized that she had indirectly ended her grandfather’s dream and destroyed his ideology. The final piece of motivation for Junna was learning from her father how Fujita’s side of the accident had gone down—with Fujita forever blaming himself for the accident rather than Junna. At this point, Junna felt compelled to do something to raise her grandfather’s spirits and reinstill his robot-loving ideology, as if she alone had the power to change things—as if she was the master of her fate and the captain of her soul.

And Junna’s actions here were, in turn, the turning point for Fujita. Seeing Junna and the Robotics Club recreate the Robot Clinic’s appearance from when it had first opened decades prior completely overturned his cynical beliefs that robots and humans should be segregated. After all, his storage robots were freely interacting with the public, and not a soul other than himself was afraid—not the children, not the adults, and not Junna. The icing on the cake was Junna and Fujita reconciling—both now with the same firm conviction about the meaning of robots.

Phase 6 is, all in all, a beautiful chapter—and more than anything, an incredible love letter to Astro Boy and its central message: robots are humanity’s friends.

But you know, the connections between Robotics;Notes and Astro Boy don’t end there. To discuss how Robotics;Notes takes things further, however, I will need to bring up context from the rest of the SciADV franchise.

This final section of the article contains spoilers for the entire Science Adventure series up to and including Anonymous;Code.

“Robots were created to be friends with humans.”

I wrote earlier about that central line from both Astro Boy and Robotics;Notes Phase 6, but there’s another meaning to it that I have yet to mention.

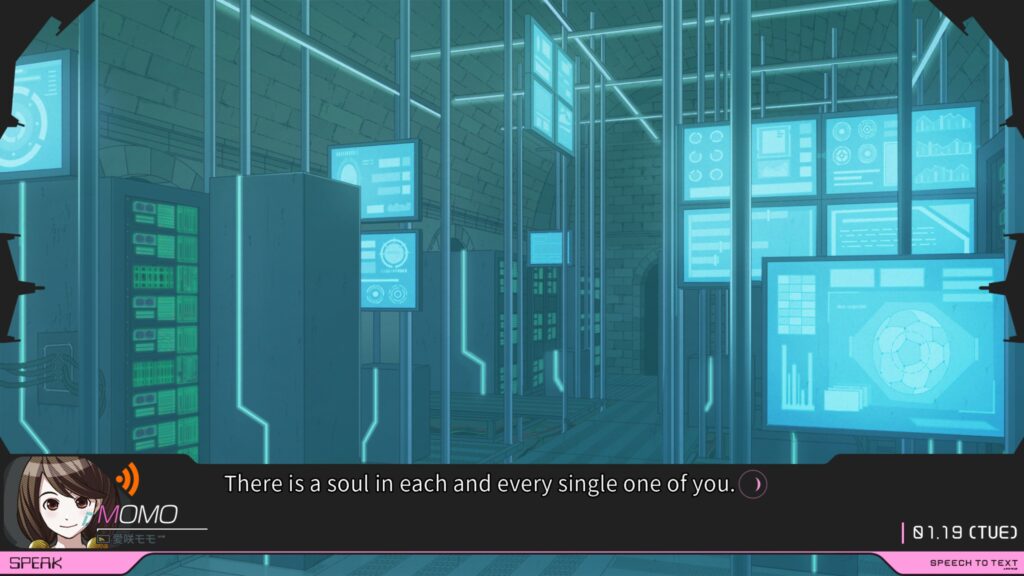

In the context of Astro Boy, this line is often used as a response when certain characters claim that robots were created to serve humans, or that robots are inferior to humans, or that robots were created to be slaves to humans with no real free will. So the idea that “robots are humanity’s friends” is really supposed to be the idea that robots, humans, and even all sorts of different alien species are equal to one another. More than that, it’s also coming from the standpoint of artificial existences all having souls and their own free will, the same way humans do. After all, you are the master of your fate, the captain of your soul.

When you look at it from that perspective, you realize that at their cores, Astro Boy and SciADV fundamentally both argue the exact same thing: that artificial existences are just as “real” or “legitimate” as physical or biological ones. In the case of Astro Boy, this is done from the standpoint of saying that sentient robots are just as legitimate as humans. And in the case of SciADV, this is done from the standpoint of arguing that AIs are just as legitimate as real people, and that even if we existed in a simulation, that wouldn’t diminish the value of our own lives. That is to say that if our world were to be fundamentally digital, that still would not make our existences meaningless—if that’s what we choose to believe. The way Robotics;Notes specifically depicts the likes of [Airi] and Sister Centipede as so legitimate as well is a further testament to that idea. They’re no different from one another, hence why they are able to exchange memories—since GAIA recognizes them as one and the same.

But let’s put the AI existences aside for now. What are robots supposed to represent? In a series about existentialism and the meaning of artificial existences, what is the significance of having an entry that focuses so heavily and intently on robots? The question sort of answers itself here—robots themselves are artificial existences. They may not be sentient the same way the AIs we see are—but they are still artificial, and they carry meaning for people nonetheless. Intriguingly enough, there’s even a moment in Phase 6 where Kaito describes Yoshiro-kun as seeming to have a will of its own despite being a robot. It’s so interesting to look back at Robotics;Notes with the understanding that the robots themselves are an allegory for everybody in the series being a programmed, artificial existence, as well as an understanding of the central message of the series that none of that matters. The robots carry so much sentimental value to people despite not being “real people.”

Special thanks to TehVict and Fasty for their help in the making of this article. Until next time, everyone! Nocchiyo!